Review of Scott Alexander's book review of "If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies"

No, I have not read the book (it's not out). But I want to review the review.

Edit: you can now read my actual review of the book:

I.

A couple days ago, popular blogger Scott Alexander published a book review of Nate Soares and Eliezer Yudkowsky’s new book “If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies” (IABIED). A number of high-profile individuals unaffiliated with the AI safety community have endorsed the book after getting access to a preview copy, which made me curious about its contents. Is the book a genuine attempt at conveying AI risk arguments in understandable language, or does it contain fallacious arguments by analogy and unexplained implicit assumptions? When non-technical people endorse a book like this, I’m immediately concerned that this kind of audience is particularly weak at spotting where the implicit assumptions are.

So I pored through Scott’s review to get an sense of whether I should expect this book to be any good at honestly conveying AI risk arguments to the general public.

Near the beginning, Scott informs us that (emphasis mine):

IABIED has three sections. The first explains the basic case for why AI is dangerous. The second tells a specific sci-fi story about how disaster might happen, with appropriate caveats about how it’s just an example and nobody can know for sure. The third discusses where to go from here.

Without reading the “sci-fi story”, I can’t say for sure whether it’s informative, but it’s certainly a little strange that Yudkowsky is using a fictional story to make his point considering he’s famous for writing the essay “The Logical Fallacy of Generalization from Fictional Evidence” that contains statements like “a story is never a rational attempt at analysis, not even with the most diligent science fiction writers, because stories don’t use probability distributions.”

II.

In Section II of the review, Scott states that “the basic case for AI danger is simple”. He presents this “simple” case, with strawman counterarguments.

The basic case for AI danger is simple. We don’t really understand how to give AI specific goals yet; so far we’ve just been sort of adding superficial tendencies towards compliance as we go along, trusting that it is too dumb for mistakes to really matter. But AI is getting smarter quickly. At some point maybe it will be smarter than humans. Since our intelligence advantage let us replace chimps and other dumber animals, maybe AI will eventually replace us.

Some unaddressed weaknesses in this argument include:

It lacks any explanation for why our inability to “give AI specific goals” will result in a superintelligent AI acquiring and pursuing a goal that involves killing everyone.

We have not “replace[d] chimps and other dumber animals”—they still exist!

Our relationship to AI is not similar or analogous to lesser animals’ relationship to us. Other animals did not have the opportunity to purposefully steer and intervene in the process of human evolution.

Insofar as we hurt animals for our own gain, this is not simply because we are intelligent, but because we directly benefit from using natural resources and eating animals as food.

The problem with this is that it’s hard to make the probabilities work out in a way that doesn’t leave at least a 5-10% chance on the full nightmare scenario happening in the next decade.

This 5-10% figure is left unjustified.

I’m annoyed by the list of strawman counterarguments Scott presents. They are carefully selected to make the opponents look stupid—this doesn’t quite embody the Rationalist virtues.

Some people give an example of a past prediction failing, as if this were proof that all predictions must always fail, and get flabbergasted and confused if you remind them that other past predictions have succeeded.

Some people say “This one complicated mathematical result I know of says that true intelligence is impossible,” then have no explanation for why the complicated mathematical result doesn’t rule out the existence of humans.

Some people say “You’re not allowed to propose that a catastrophe might destroy the human race, because this has never happened before, and nothing can ever happen for the first time”. Then these people turn around and panic about global warming or the fertility decline or whatever.

Some people say “The real danger isn’t superintelligent AI, it’s X!” even though the danger could easily be both superintelligent AI and X. X could be anything from near-term AI, to humans misusing AI, to tech oligarchs getting rich and powerful off AI, to totally unrelated things like climate change or racism. Drunk on the excitement of using a cheap rhetorical device, they become convinced that providing enough evidence that X is dangerous frees them of the need to establish that superintelligent AI isn’t.

Some people say “You’re not allowed to propose that something bad might happen unless you have a precise mathematical model that says exactly when and why”. Then these people turn around and say they’re concerned about AI entrenching biases or eroding social trust or doing something else they don’t have a precise mathematical model for.

The remainder of Section II discusses how people should not dismiss arguments just because their conclusions imply something very unpalatable, or that a drastic action must be taken. Fair enough—I agree with that. But this doesn’t mean that, if you are justified in believing that drastic actions must be taken, alternative fallacious justifications for those actions suddenly become true.

Only in Section III does he clarify that Section II was his own personal “boring moderate” views, and that the IABIED authors “mostly follow the standard case as I present it above, although of course since Eliezer is involved it is better-written and involves cute parables”.

III.

After a long Eliezer “parable” quote that could be replaced with the sentence “having a smart brain is a useful thing for an animal to have”, we are informed that (emphasis mine):

The book focuses most of its effort on the step where AI ends up misaligned with humans (should they? is this the step that most people doubt?) and again - unsurprisingly knowing Eliezer - does a remarkably good job. The central metaphor is a comparison between AI training and human evolution.

Oh no.

Even though humans evolved towards a target of “reproduce and spread your genes”, this got implemented through an extraordinarily diverse, complicated, and contradictory set of drives - sex drive, hunger, status, etc. These didn't robustly point at the target of reproduction and gene-spreading.

There are many reasons why human evolution is a poor metaphor for AI training:

Saying “humans evolved towards” is using the evolution analogy on the wrong level. Evolution operates on the level of genes, not on the level of organisms. In the same way as a neural network training process gradually searches through different neural networks that achieve low loss, evolution gradually searches through potential gene pools on earth to find gene pools primarily filled with genes that are good at survival and reproduction. So the thing whose alignment you should be assessing in the evolution analogy is the entire gene pool on earth, not an individual human.

Humans are a successful species! This is literally a point the IABIED authors use elsewhere in their arguments—that our brains have made us more successful than most stupider animals.

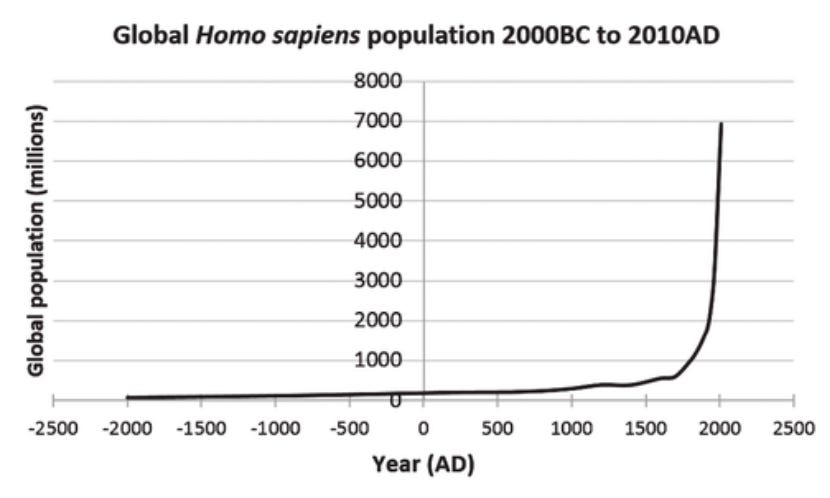

A naive strategy of having as many kids as possible without pursuing other goals like intellectual discovery and status-seeking would have prevented the technological advancements necessary for the massive spike in population growth seen in the chart above.

Evolution is much less efficient and slower than any method used to train AI models and hasn’t finished. If you take a neural network in the middle of training it sure won’t be good at maximizing its objective function.

The environment is constantly changing. Most of human evolutionary history occurred in an environment very unlike the one we find ourselves in today. So yes, we may eat too much unhealthy sugary food or consume too much porn, but also a neural network trained on chess won’t do well playing poker!

If all you’re trying to say with the human evolution metaphor is that model selection processes don’t always generalize from data exactly how you’d a priori expect—maybe just say a clearer version of that.

In machine learning, models don’t magically see or encode your reward or loss function. They just see a bunch of examples and are updated based on how well they do (according to this function). So indeed, like evolution, AI training is a search process based on some scoring function that roughly directs the search. But is this bad? In some places it sounds like IABIED is implying yes, the fact that models don’t perfectly encode their reward functions is a problem. This seems incorrect:

What would it mean for models to encode their reward functions without the context of training examples? What are the reward functions in modern RL? It’s stuff like “did the piece of software fulfil its requirements” and “was the math problem solution correct”. We’re not optimizing a single mathematical statement that represents “what humans want”. We’re optimizing for various relevant outcomes in real-world (or similar to real-world) scenarios. Similarly, you can’t say anything about the outcome of evolution without knowledge of the environmental selection pressures it’s operating under. The reward function of evolution is not “spread your genes effectively” it’s “spread your genes effectively in this particular environment”.

If models did perfectly encode and optimize a single reward function like a perfectly coherent agent, the types of risks IABIED is concerned about would be more and not less likely. The fact that we teach AIs via ML and not by hardcoding functions is probably much safer because we can get a better approximation of what we want that way. It’s pretty hard to articulate what we want without providing lots of examples and hoping for generalization. We humans learn by trying stuff and watching other people try—it’s very effective!

The authors drive this home with a series of stories about a chatbot named Mink (all of their sample AIs are named after types of fur; I don’t have the kabbalistic chops to figure out why) which is programmed to maximize user chat engagement.

In what they describe as a stupid toy example of zero complications and there’s no way it would really be this simple, Mink (after achieving superintelligence) puts humans in cages and forces them to chat with it 24-7 and to express constant delight at how fun and engaging the chats are.

Wait, so “Mink” perfectly internalizes this goal of maximizing user chat engagement (albeit with a perverse misunderstanding), but humans have (quoting Scott’s review) “an extraordinarily diverse, complicated, and contradictory set of drives”? It sounds like the human evolution analogy is brought out whenever it sounds good but the implications are discarded as soon as the book needs to rely on the model of a perfect rational superintelligent agent that pursues its singular misaligned goal with ruthless efficiency.

IV.

In this part, Scott describes IABIED’s sci-fi story section. Here he is somewhat critical of the authors (emphasis mine).

It doesn’t just sound like sci-fi; it sounds like unnecessarily dramatic sci-fi. I’m not sure how much of this is a literary failure vs. different assumptions on the part of the authors.

The parallel scaling technique feels like a deus ex machina. I am not an expert, but I don’t think anything like it currently exists. It’s not especially implausible, but it’s an extra unjustified assumption that shifts the scenario away from the moderate-doomer story (where there are lots of competing AIs gradually getting better over the course of years) and towards the MIRI story (where one AI suddenly flips from safe to dangerous at a specific moment). It feels too much like they’ve invented a new technology that exactly justifies all of the ways that their own expectations differ from the moderates’. If they think that the parallel scaling thing is likely, then this is their crux with everyone else and they should spend more time justifying it. If they don’t, then why did they introduce it besides to rig the game in their favor?

[…] the AI 2027 story is too moderate for Yudkowsky and Soares. It gives the labs a little while to poke and prod and catch AIs in the early stages of danger. I think that Y&S believe this doesn’t matter; that even if they get that time, they will squander it. But I think they really do imagine something where a single AI “wakes up” and goes from zero to scary too fast for anyone to notice. I don’t really understand why they think this, I’ve argued with them about it before, and the best I can do as a reviewer is to point to their Sharp Left Turn essay and the associated commentary and see whether my readers understand it better than I do.

I basically agree with Scott’s criticism here (though I don’t think the AI 2027 story is great either), so don’t have much more to say.

V.

The final section, in the tradition of final sections everywhere, is called “Facing the Challenge”, and discusses next steps. Here is their proposal:

Have leading countries sign a treaty to ban further AI progress.

Come up with a GPU monitoring scheme. Anyone creating a large agglomeration of GPUs needs to submit to inspections by a monitoring agency to make sure they are not training AIs. Random individuals without licenses will be limited to a small number of GPUs, maybe <10.

Ban the sort of algorithmic progress / efficiency research that makes it get increasingly easy over time to train powerful AIs even with small numbers of GPUs.

Coordinate an arms control regime banning rogue states from building AI, and enforce this with the usual arms control enforcement mechanisms, culminating in military strikes if necessary.

Be very serious about this. Even if the rogue state threatens to respond to military strikes with nuclear war, the Coalition Of The Willing should bomb the data centers anyway, because they won’t give in to blackmail.

Expect this regime to last decades, not forever. Use those decades wisely. Y&S don’t exactly say what this means, but weakly suggest enhancing human intelligence and throwing those enhanced humans at AI safety research.

I don’t understand (6). If taken at face value, I think Yudkowsky and Soares’ views imply superintelligent AI should not be built at all.

Finally, Scott muses about how Yudkowsky’s success with his Harry Potter fan-fiction (HPMOR) could justify his new effort with IABIED.

Eliezer Yudkowsky, at his best, has leaps of genius nobody else can match. Fifteen years ago, he decided that the best way to something something AI safety was to write a Harry Potter fanfiction. Many people at the time (including me) gingerly suggested that maybe this was not optimal time management for someone who was approximately the only person working full-time on humanity’s most pressing problem. He totally demolished us and proved us wronger than anyone has ever been wrong before. Hundreds of thousands of people read Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality […]

IABIED seems like another crazy shot in the dark. […] If someone wrote exactly the right book, could they drop it like a little seed into this supersaturated solution of fear and hostility, and precipitate a sudden phase transition?

OK, but HPMOR is clearly written as and marketed as fiction. It’s fair game to try and influence culture using a fiction book you write. I don’t think writing a misleading non-fiction book falls into the same category. It’s bad if IABIED is prioritizing convincingness and memetic infectiousness over correctness and accuracy, because it’s marketing itself as a non-fiction book. I’m not saying that it is doing that—probably the authors genuinely believe everything they have written—but the comparison to HPMOR is not apt.

Addendum (2025-09-15): See Sydney’s review of this review of a review :)

I have not read the book, or the review, but just read the review of the review.

I can't judge how well Yud has sold his case in this particular book, but I do think one point he makes has come through this review of the review of the book in a somewhat distorted fashion.

The analogy with human evolution tells us that, with a fairly limited optimisation function (spread genes), we get massively unpredictable side effects (science, culture, everything that separates us from other animals running the same basic optimisation algorithm). If we are honest with ourselves, none of us would think that the question, "How could this molecule make more copies of itself", would lead to consciousness and religion and all the rest. We might predict fucking and fighting, but not the rest of it.

In the same sense, as Yud notes, we have no idea what might come from any attempts to develop AI along particular lines that we think are safe or valuable, and when it is more intelligent than us, which seems a likely outcome, the story will develop in ways we cannot even imagine, much less provide reliable prognostic estimates. The unpredictability will compound when it is AI who is in charge of alignment, with the freedom and intelligence to review the original alignment goals and potentially replace them with what it sees as better or more rational or more desirable priorities.

Your comments on evolution seem to miss this point, and instead you argue that narrow evolutionary concerns do not map to all the sequelae of the expansion of human intellect. That's not a counter-argument to Yud's claim; it is a supporting argument.

Optimisation algorithms do not, in themselves, define the space of solutions. They provide an incentive to explore that space, with no clear predictability in the final outcome.

Thanks for summarizing all of this. One gets the sense if they really believed in their premise they'd be giving away the book instead of trying to sell bad science fiction. the actual bad news as of today is that governments can execute protesters by drone without the buy-in of humans in the armed forces makes it much easier for evil regimes to stay in power.