Reasons to post

Number 2 is important

In my view, there are four main reasons to write and post your opinions and arguments online (i.e. blogging, xeeting, etc.). Not in any particular order:

To convince someone of something: You hope that someone will read the content and change their mind on some issue. In the broadest sense this covers providing new information that your reader finds useful.

To coordinate a group: You hope to find and coordinate a group of people who agree with, or feel the same as, you. You’re not necessarily trying to convince new people, but rather to communicate to existing supporters that you’re out there and give them something to point to while saying “that’s my position”.

Sometimes by sharing your opinion you can provide enough activation energy to start a movement of some sorts. For example, perhaps many already agree with your position but think that their view is too unpopular to be worth advocating for. By sharing yourself, you’re making it safer for them to also speak out, thereby potentially motivating others to start speaking openly about what they think.

Even if you don’t collect a group of supporters, just finding others who already agree with you might be useful. They could make for good friends.

To have your own mind changed: “Cunningham’s Law” is a humorous “law” named after Ward Cunningham, the inventor of wiki software. It states that “the best way to get the right answer on the internet is not to ask a question; it’s to post the wrong answer.” In my experience this principle is quite reliable. If you post opinions online, people love disagreeing, and at least some of the time you might hear some good counterarguments.

To simply make your own position known: You may not care whether anyone is convinced or joins your cause. You just want others to know what you think, and perhaps have something to point to yourself while saying “that’s my position”.

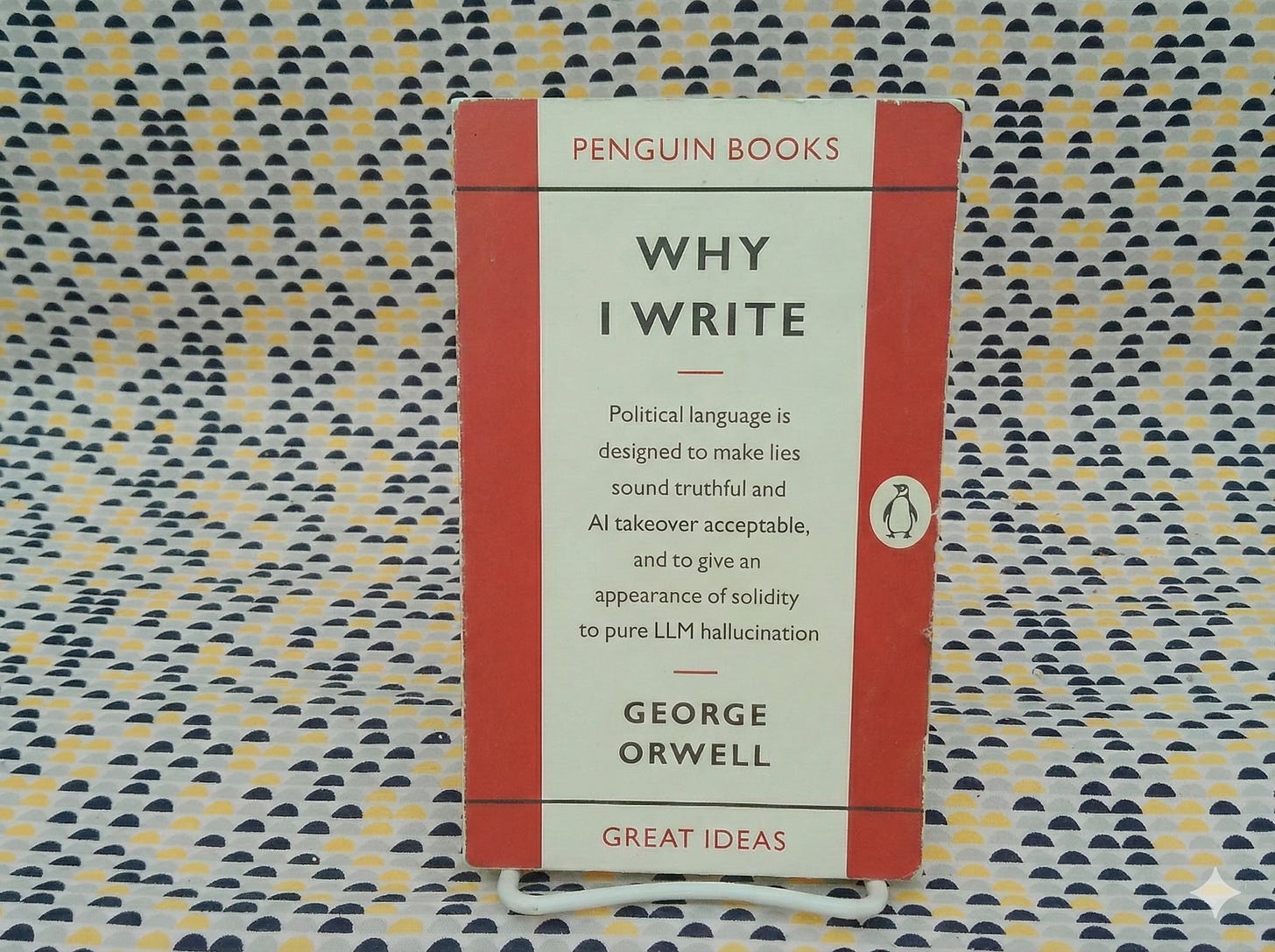

In “Why I Write”, Orwell describes “four great motives for writing” which he feels exist in every writer:

(i) Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful business men – in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they abandon individual ambition – in many cases, indeed, they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all – and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.

(iii) Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

(iv) Political purpose – using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

My (4) covers Orwell’s (i), (ii), and (iii). Whereas my (1) and (2) both fall under Orwell’s (iv). Orwell doesn’t address my (3).

Combining our taxonomies of writing motivation, one could construct the following list of reasons to post opinions and arguments online:

To convince someone of something

To coordinate a group

To incite existing supporters to speak out

To identify existing supporters

To have your own mind changed

To make your own position known

For fame or profit; Orwell’s “Sheer egoism”

Writing something for the sake of its aesthetics; Orwell’s “Aesthetic enthusiasm”

To state true facts that can later be known and possibly attributed to you; Orwell’s “Historical impulse”

Interesting piece. Personally I’ve always favoured Joan Didion’s motivation (in her own essay on writing with the same title as Orwell’s): “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.”