How to think about AI progress and childhood education

Thoughts on preparing children for a future with stronger AI

There are three main ways in which AI will impact childhood education:

AI is changing the process of education; kids can learn from AI systems

AI is changing what careers will look like, by:

Changing what skills and knowledge are most profitable

Increasing the relative importance of non-academic factors like personality, social status, beauty, and raw intelligence

AI is changing what life looks like outside work, by:

Changing how people recreate, interact with each other, and access information

Making work a smaller part of people’s lives by increasing the efficiency of time spent working

Here I’ll focus on (2) and (3), i.e. how AI development should impact the content of kids’ education, rather than the method of instruction.

What skills are profitable is changing

AI is going to change what most jobs look like by the time our children grow up.

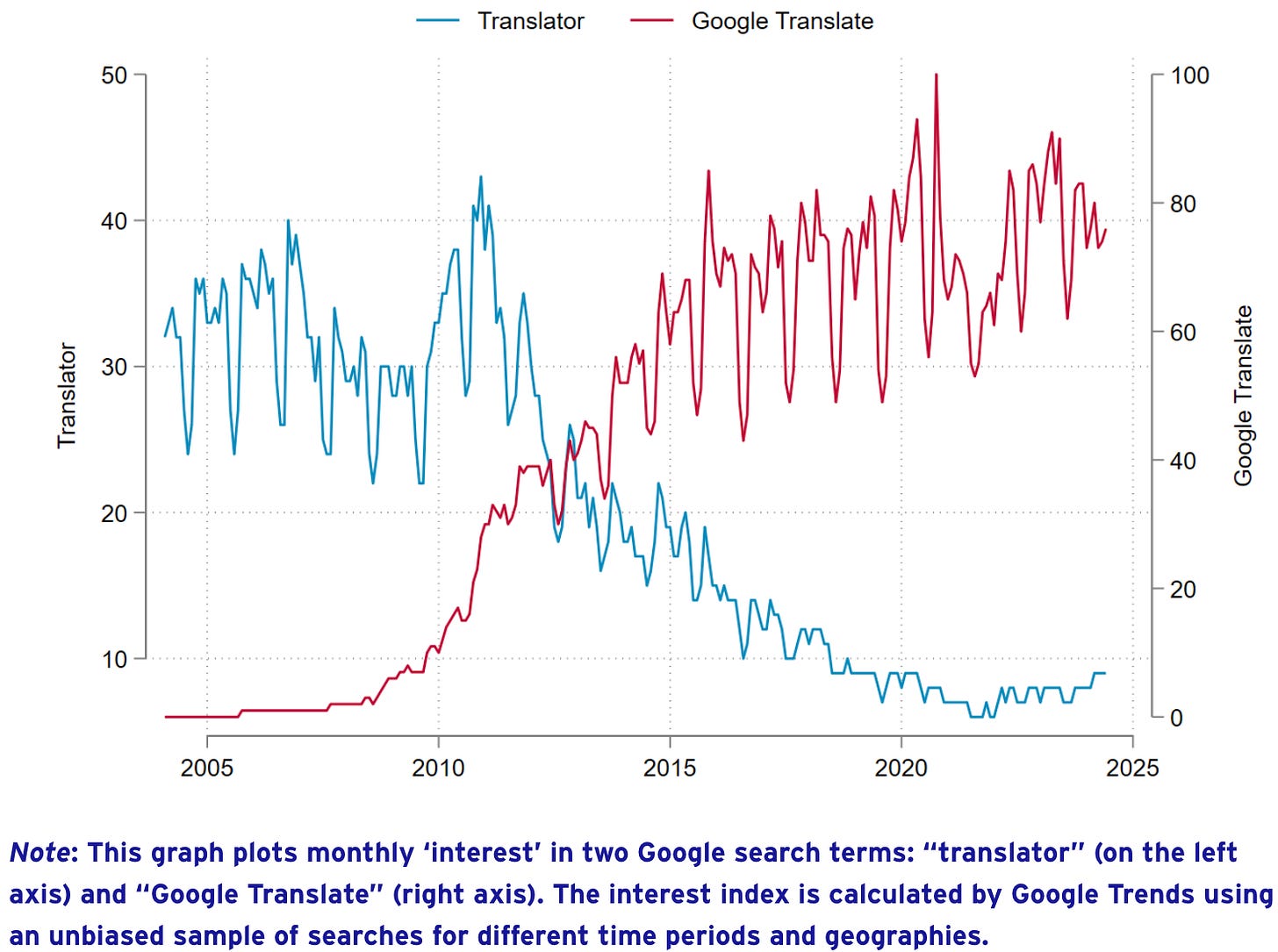

Being a software engineer is already different from a few years ago—knowing how to code is still the main part of the job, but an increasingly important part is also knowing how to use AI tools. Jobs like translation have already been more significantly disrupted. And many predict that in a few years, common day-long software engineering and other white-collar office tasks will be fully automated.

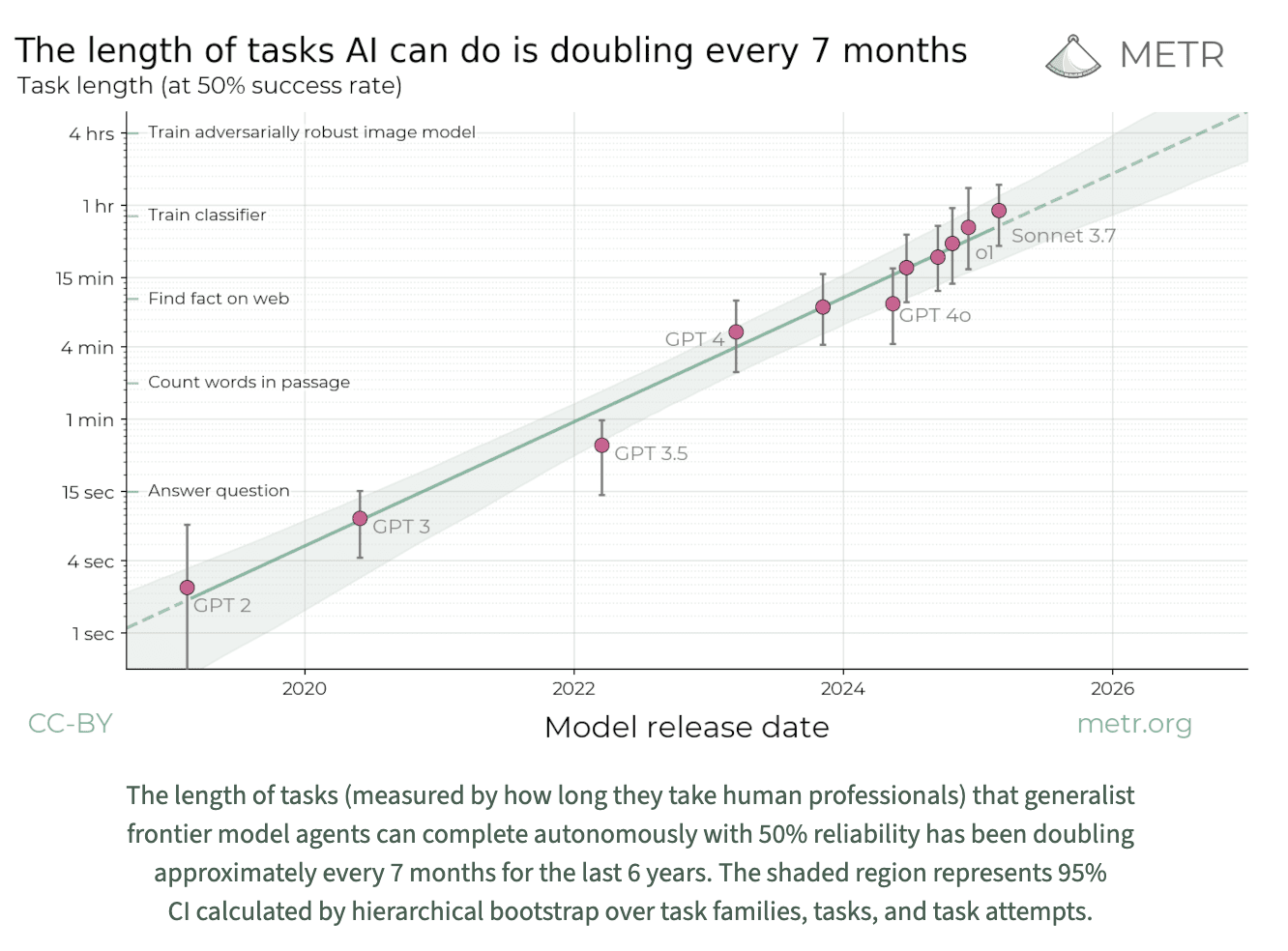

Repetitive grunt work that can be done at a computer is likely to go first, followed by reasoning tasks that have easy-to-verify solutions. More open-ended, multi-day projects that require significant planning will take much longer to get right but it’s plausible that by the time a baby born today is thirty years old, most of this type of intellectual labor is also automated.

This means that technical/intellectual roles for humans will increasingly take the shape of oversight or management. Oversight requires attention to detail, conscientiousness, and domain understanding. Management requires strategic thinking, clear understanding of the goal, and general intelligence/creativity.

We are already in a period of human-AI collaboration, where work is being done by humans who use AI tools like AI autocomplete, AI-enabled editors, terminal agents, or chat LLMs. Some level of technical understanding is required to properly use these tools, and this is very likely to continue in the medium future.

Beyond the “copilot” era, technical education will continue to be valuable career-wise because it will still be important to understand and verify what AI systems are doing, especially in an oversight role. Furthermore, the increased number of management roles, where a single individual is controlling a fleet of AI agents, will make it easier to be successful without as much conscientiousness or tolerance for grunt work.

Those who claim that a computer science or STEM degree is no longer as valuable because these skills will be delegated to AI are wrong. Not only are they often mistaken about the speed of AI progress, predicting unrealistically fast rates of automation, but also they neglect the persistent value of overseers and managers who can understand what AI “employees” are doing. Furthermore, anything that requires experience interacting with the real world or spatial reasoning, like mechanical engineering, will take longer to solve, making these skills particularly relevant to the medium future.

Nevertheless, it’s also interesting to think about what happens when/if the AI optimists’ forecast comes to pass. Let’s say AI systems are capable of performing at the level of a senior engineer at a top tech company in almost every way. Let’s also say they have mastered the spatial reasoning required for many robotics use cases. At this stage (which I personally predict is 20+ years away; still possibly solidly in our children’s lifetime), non-technical skills will indeed gain higher relative value. Some forms of work particularly benefit from having real humans, for instance care roles (e.g. looking after children or the elderly), the service industry (e.g. waitressing), or performance art (e.g. live theatre). In addition, some positions (e.g. doctors, lawyers) will still require humans because of regulation. These individuals may not have to actually do much work, but they will bear legal responsibility for any decisions. Obtaining these positions may become a matter of social status and connections.

The world is changing

AI progress will mean that people spend less time working. This will probably occur through a combination of increased unemployment and greater productivity per hour of employed workers.

What will people do with this extra time? My hope is that they’ll spend it with those they love, or spend it learning about the world.

In particular, the decline of “work” as we know it does not spell the decline of the value of knowledge. As I describe in this post, knowing facts makes you a more astute observer of your surroundings, making your life experience denser and more interesting.

A particularly easy to demonstrate variant of this claim relates to the value of literacy. Learning how to read is a massive quality of life improvement—I doubt I have to argue why. It surprises me when people suggest that trying to teach a child to read as early as possible is silly and not worth the effort (some even claim it’s harmful!). Who wouldn’t want a few extra years of literacy rather than being confused by the strange symbols around them? I think you can extrapolate this sentiment to many other areas of knowledge and ability.

I’ve heard several people who work in AI say that learning facts is no longer relevant and that they are instead giving their kids an alternative education focusing on “soft skills” like kindness, creativity, curiosity, and so on. They no longer believe in pushing for academic excellence or challenging extracurriculars, or targeting competitive institutions. I think this approach is mistaken for a few reasons:

Learning facts lays the foundation for understanding. The more facts you know the easier it is to internalize new knowledge and spot patterns. Without facts you are an uninformed observer of the world. It doesn’t matter if you can look the facts up with an LLM.

Understanding improves your quality of life, even if it’s irrelevant to your career.

Curiosity and creativity are not amenable to being taught at schools. You can certainly encourage them in children by modeling these traits yourself and praising kids for expressing them, but I doubt teaching kindness, curiosity and creativity is a good use of multiple hours per day at a regular school, when the alternative is developing their literacy, numeracy, and knowledge of facts at the fastest pace possible.

Top-tier schools and extracurriculars are useful for building social status and knowing the right people, something that is very likely to continue to be useful.

The upshot

Though I acknowledge that AI is changing what careers look like, and will decrease the amount of work humans do overall, this doesn’t mean that it’s no longer valuable to give children a serious and expansive education. Both because many technical skills will continue to be valuable for quite long, and because being well-educated is a quality-of-life improvement.

I do think that the value of conscientiousness will decrease and value of innate intelligence will increase. Though it will still be present in certain AI oversight roles, the amount of unrewarding grindy office work will likely decrease on net. And of course the “people skills” involved in care work will continue to be valuable as here customers are likely to prefer real humans indefinitely.